Comprehensive panels of “reversion mutations” found in general circulation look like an experiment

“psmi

Aug 25, 2023

On August 5th 2023 a Japanese research team published a pre-print that appears to contain the most important and shocking revelations of the covid era.

Atsuki Tanaka and Takayuki Miyazawa, of Osaka Medical University and Kyoto University, wanted to trace the historical evolution of the omicron variant of SARS-CoV2 by studying viral sequences found “in the wild” and deposited in public databases.

In doing this they found around 100 separate omicron subvariants that could not conceivably have arisen through natural processes. The existence of these variants seems to provide definitive proof of large-scale lab creation and release of covid viruses.

Moreover the variants appear to form comprehensive panels of mutations typical of those used in “reverse genetics” experiments to systematically test the properties of different parts of viruses.

The authors also found exact matches to omicron variants in sequences originating from Puerto Rico which were deposited in databases in 2020 – over a year before the announcement of the discovery of omicron in South Africa.

Coupled with observations of implausibly low numbers of “silent” mutations in SARS-CoV2 variants, Tanaka and Miyazawa argue that all variants emerging since the original Wuhan outbreak are unnatural, and speculate that they represent an experimental program to test determinants of the infectivity and pathogenicity of SARS-CoV2 in the global population.

Background: natural evolution proceeds by the accumulation of mutations

Before describing the study and its findings, it’s worth quickly reviewing the basic principles of evolution of viruses (and all life forms). Feel free to skip this if you know it.

SARS-CoV2, like all viruses and organisms, is defined by its genetic information – which can be thought of as a string, or sequence of letters. In most organisms the string is made of DNA, but SARS-CoV2 and some other viruses use strings of RNA, a closely related molecule, to provide this information storage function.

The genetic material (DNA or RNA) is divided into “genes” – stretches of genetic sequence that each encode a protein. Proteins are active molecules which are synthesised by the cell, using the gene as a blueprint. Proteins are also sequences, but with very different building blocks. They don’t exist as simple strings that just store information, but instead form complex 3D structures which have biological activity.

When an organism reproduces itself the genetic sequence (DNA or RNA) is copied and passed on to the next generation. But the copying mechanism is error-prone, and occasionally a change, or “mutation” will be made. Successive generations will pass on this sequence, so mutations naturally accumulate over time.

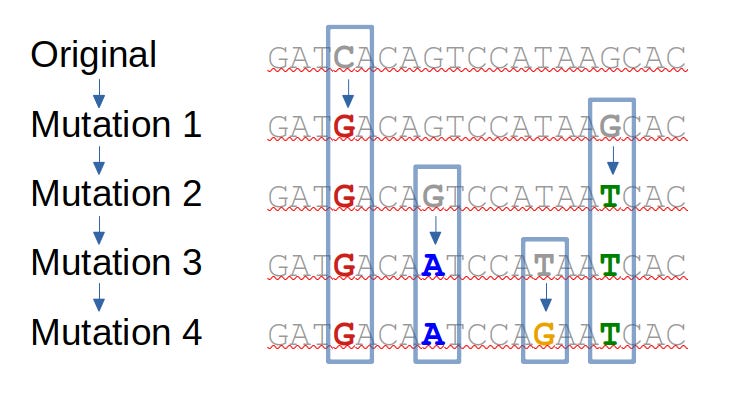

The diagram below illustrates how this happens – with an original DNA sequence accumulating 4 successive mutations.

The effects of mutations on the organism determine whether they persist in nature

It’s useful to consider that there are a few different general types of mutation, as judged by their effects on the organism:

- Many will have no effect. Some individual changes of a letter of DNA/RNA will not actually change the sequence of the protein encoded. Such “synonymous” mutations usually have no effect, so they simply accumulate over time in natural evolution. As we shall see, the lack of synonymous mutations is an important sign that the evolution of omicron and other variants is not natural.

- Of those that do have an effect, the vast majority will be deleterious – for the same reason that randomly changing part of any functioning system is likely to break it. Such mutations will disappear quickly from the population.

- Very rarely a mutation will cause a change with a beneficial effect. These mutations will then proliferate in future generations – as organisms carrying them will survive and reproduce more effectively.

So all life forms progressively accumulate mutations – some silent, and some beneficial. This is evolution.

The “unnatural evolution” of omicron

Let’s now consider the specific case of the omicron variant of SARS-CoV2 and it’s (presumed) evolution from the original Wuhan strain.

For this article we’ll follow Tanaka and Miyazawa in focusing on just one section of the virus’ string of genetic information – the gene encoding the notorious spike protein. They consider three officially-recognised variants of omicron – BA1, BA1.1 and BA2. For the moment we’ll just look at BA1.

As with all evolution, changes in the spike protein occur through progressive accumulation of mutations in the genetic sequence that encodes it. In the case of omicron BA1 there are 37 non–synonymous mutations – that is, points where the sequence of the spike protein produced is different to that of the original Wuhan variant.

Tanaka and Miyazawa wanted to use public databases, where researchers from around the world deposit the viral sequences they have found, to trace the evolutionary history of the omicron BA1 spike protein – that is, to answer the question: in what order did these 37 mutations accumulate?

Tracing the order of accumulation of omicron mutations

There are two obvious ways to go about this – work forward or backward.

In the forward approach, you could look in the databases for versions of the sequence that have just one of the 37 omicron mutations, but which are otherwise identical to the original strain. This lone mutation must have been the first. You could then repeat the process to identify the second, third etc.

However variants carrying very early mutations would have been rare in the global population of SARS-CoV2, and may not appear in the databases.

A surer approach, and the one taken by Tanaka and Miyazawa, is to work backwards instead. That means starting by working out which of the 37 mutations is the last, or most recent.

To do this you need to find a sequence that includes all the mutations except one – and this must be the most recent mutation.

So Tanaka and Miyazawa made a series of 37 database queries using sequences each lacking just one of the omicron BA1 mutations – reasoning that one of the 37 should find a match, indicating the last mutation in the evolutionary progression to BA1.

It’s interesting to imagine yourself in the position of these researchers, running queries for each of the 37 mutations, perhaps wondering which of them would turn out to be the most recent, and getting the answer.. ..ALL OF THEM*.

Well, all but 1 – which makes no material difference.

Their brains must have exploded.

A panel of variants with individually-reversed omicron BA1 mutations cannot arise naturally

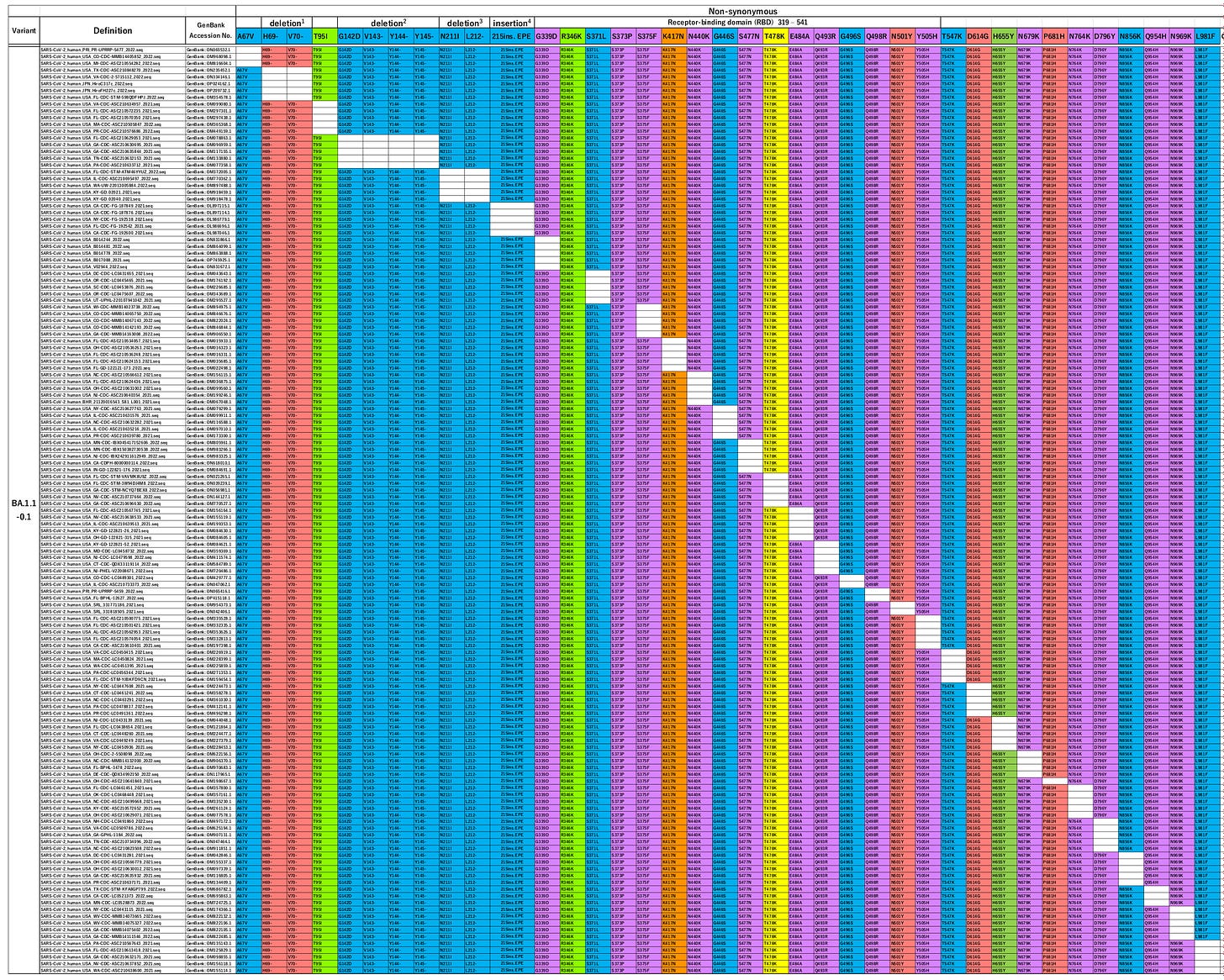

In the figure below (Fig 2A from the paper), each row represents a variant of omicron BA1 found “in the wild”.

The columns represent each of the omicron mutations. If the cell is colored, that means the variant carries the mutation. White cells show the mutation is missing, and the spike protein sequence is identical to the original Wuhan strain at that point.

If you think the table looks awfully neat, you’re right. It shows that, for all but one mutation in the omicron sub-variant BA1, a strain exists in which that mutation – alone – is absent.

In natural evolution by accumulated mutation, each variant only has one parent – because it was created by a single mutation event. So, taken at face value, these results imply that one of the variants is the parent of omicron BA1 (we cannot tell which), and all the others are children.

We can now answer Tanaka and Miyazawa’s original question and state the natural history of omicron BA1 evolution implied by these results:

- The officially-recognized BA1 strain forms when the last of its 37 mutations occur (we don’t know which this is);

- BA1 then undergoes 35 separate, parallel changes that each perfectly reverse one of those mutations to the sequence of the original Wuhan strain.

This is absurd. Perfect reversion of mutations like this, on such a scale, is completely implausible by any natural process.

The variants found by Tanaka and Miyazama can best be described as a “panel” of reversion mutations. This kind of panel is exactly what a researcher would create to systematically test the contribution of different elements of a virus to its activity.

Comprehensive reversion “panels” are also found for other official omicron variants

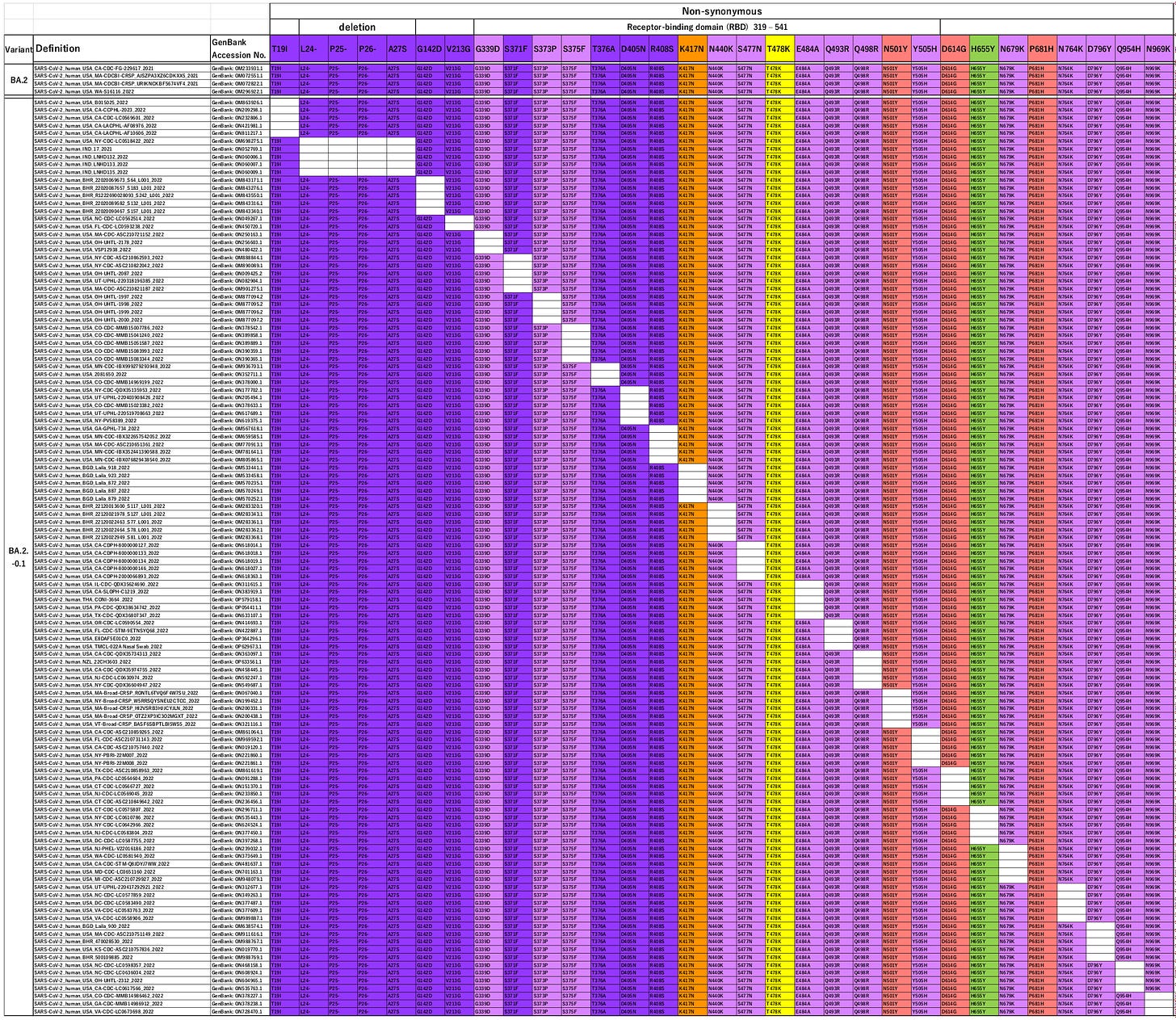

The researchers also looked at two further recognized omicron variants in wide circulation: BA1.1 and BA2. Remarkably they found the same “panels” of reversion mutations for both of them.

BA1.1 is very similar to BA1 – it only has one additional mutation, compared to the Wuhan strain, for a total of 38.

When Tanaka and Miyazawa made queries missing out each of these mutations individually they found 37 of the 38 existing “in the wild”.

BA2 is fairly different to BA1 – they share 14 mutations with respect to the Wuhan strain, but BA2 only has 17 further (different) mutations for a total of 31.

When they looked for variants missing these individual mutations they found 29 of the 31 “in the wild”.

“Recombination”, or swapping of genetic material between different viruses cannot explain the Omicron variants either

The discussion above relates to evolution by progressive accumulation of mutations, in which each new variant is produced by mutation of a single parent.

There is another mechanism by which viruses and other life forms can evolve. “Recombination” involves swapping sections of genetic material between two different variants. Could the variants observed be formed by swapping genetic material between omicron BA1 and the original Wuhan virus?

Tanaka and Miyazawa go to some lengths to consider this possibility, but are easily able to exclude it.

For one thing, recombination would require omicron BA1 viruses and other ancestral viruses to be present in the same cell at the same time – because recombination can only occur in a cell, during the replication phase of the virus. This will be extremely rare given the frequencies involved, and the requirement to create so many reversion mutations – particularly given the timing of waves of the different variants, as discussed in the paper.

Explaining these reversions by recombination would mean a section of RNA in omicron BA1 containing the mutation to be reversed would have to be cleanly swapped, such that the mutations to either side were unaffected. There would have to be two “cross-overs” between the variants, one on each side of the mutation. But cross-overs require alignment of a stretch of common sequence between the two strains. For some mutations, the gap either side to the next mutation is simply not large enough to accommodate these cross-overs, and recombination is therefore impossible.

Recombination would also leave its marks in the flanking regions of the virus either side of the spike protein gene – and these were not found.

Omicron variants in samples from Puerto Rico – over a year before omicron’s official detection

So Tanaka and Miyazawa were able to show that recombination could not explain the panel of reversion mutations they found. But in considering this possibility they stumbled on even more evidence that raises fundamental questions about omicron’s history.

As they conducted database queries to look for signs that recombination had been involved, they found a matches to a sequence from Puerto Rico that was submitted in 2020. Further searches found 29 variants attributed to Puerto Rico that exactly match either omicron BA1 or BA2, based on spike protein sequences.

All these sequences were deposited in the database in 2020, over a year before detection of omicron in South Africa was announced in November 2021.

Lack of “synonymous” mutations strongly suggest artificial origins of SARS-CoV2 variants

As if all that weren’t enough, Tanaka and Miyazawa point out another line of evidence that of itself is probably enough to conclude that omicron variants are unnatural.

The explanation of mutations above pointed out that in nature you expect to see:

- some that have some material and beneficial effect on the organism; and

- some that are “silent” or “synonymous” which do not affect the proteins produced from the RNA/DNA, and should not change the organism’s ability to reproduce

These “synonymous” mutations which don’t actually change the corresponding protein are, as you might expect, initially far more common than those which affect the protein itself. They usually would have no effect on the ability of the virus to survive, so they just accumulate naturally over time, alongside the more functionally meaningful acquisition of rarer beneficial non-synonymous mutations.

But the official omicron variants mentioned here all have just a single synonymous mutation in the gene encoding the spike protein – as compared to 31 to 38 non-synonymous mutations.

This makes no sense. Natural evolution would always be expected to create silent synonymous mutations at a greater rate than non-synonymous mutations that can only persist if, against high odds, they randomly result in a design improvement to the protein they encode.

The authors go on to point out that this implausible observation is not limited to omicron:

There were no synonymous mutations in the Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta, or Mu variants, [and] only one each in the Lambda and Omicron variants.

Omicron reversion panels appear to be part of a systematic experiment

The presence “in the wild” of almost complete panels of perfect individual reversions of virtually every mutation in 3 separate omicron lineages cannot plausibly be natural. Instead it looks exactly like a systematic exercise in “reverse genetics” to test the effects of each omicron mutation on the virus’ behaviour.

It’s clear that some or all omicron variants were synthesised in a laboratory from which they were somehow released, as part of a deliberate program. Coupled with the lack of synonymous mutations in other variants, this suggests that all variants described after the original Wuhan strain have artificial origins.

The authors suggest the variants they have found are indeed part of an experiment to characterize the spike protein and the effects of mutations on the virus’ behaviour:

Indeed, the lack of findings to date that many of the various mutations seen, especially in the early variants, are indeed associated with increased viral infection (van Dorp et al, 2020) supports the hypothesis that each variant was artificially synthesized to identify the amino acids of the S protein responsible for infectivity and pathogenicity.

Conclusion: this changes everything

If the observations and inferences in this paper are correct – and barring a pure hoax, involving fraudulent depositions to sequence databases, they certainly seem to be – then they provide indisputable evidence that the entire history of SARS-CoV2, at least subsequent to the emergence of the original strain, is artificial.

Someone, somewhere, really is doing all this deliberately.

Corrections

3 Sep 2023

- Some

Mostindividual changes of a letter of DNA/RNA will not actually change the sequence of the protein encoded.

The majority of random single mutations will actually change the amino acid encoded. But the overwhelming majority of these will simply mess up the protein, so it’s still true to say that synonymous silent mutations should initially outnumber functional mutations.

Subscribe to psmi’s Substack

Launched 20 days ago

All beasts, they hunger, and eat, and die, and so do we, and the world ‘s a sty. So hush, fellow swine, why nuzzle and cry?”

Leave a Reply